Tag Archives: assessment

How do we know they are learning?

It’s one thing saying children learn through play, but it’s another thing trusting it. We’re compelled to look for the evidence. The evidence is right there. All we need to do is look.

Who am I as a learner?

Making progress

One purpose of documenting children’s learning is to be able to capture the progress in children learning. The word progress can be defined as ‘the forward or onward movement toward a destination’. So with that definition in mind we have to think about what is the destination we are moving towards?

Te Whāriki aspiration provides us with that destination

” … that all children will grow up as competent and confident learners and communicators, healthy in mind, body and spirit, secure in their sense of belonging, secure in the knowledge that they make a valued contribution to society.”

Te Whāriki also provides us with the desired outcomes for our children

- Mana atua = I have power over myself. I know my own strengths. I value my whakapapa.

- Mana reo = I share my views. I ask for what I need. I express my ideas.

- Mana auturoa = I explore the bigger world.

- Mana tangata I take care of others. I take leadership.

- Mana whenua = This place is my turangawaewae. I join in.

Margaret Carr developed a notion of progress here as the ABCD framework – where the measure of progress involves four key elements – agency, breadth, continuity and distribution.

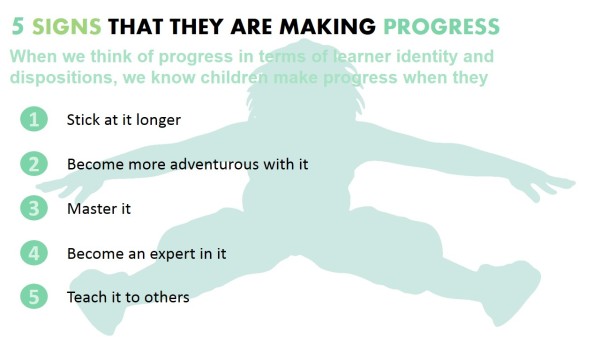

We can also think of progress in terms of learner identity and dispositions. We know children make progress when they

- Stick at it longer

- Become more adventurous with it

- Master it

- Become an expert in it

- Teach it to others

Learning stories provide us a powerful tool to capture this learning. A learning story generally captures a moment in time to illustrate the child’s learning. A learning story can also capture a child’s learning over a longer period of time – this will provide a holistic picture of the child as a learner. Below are three examples of what that might look like.

A progress story focusing on the sparkling moments

A progress story focusing on the strands of Te Whariki

A progress story focusing on the strands of Te Whariki

End of session korero

In Playcentre the end of session korero is pounamu. It’s a time to stop and reflect, to connect, to share stories and to learn from each other. When thinking about documenting it, it’s a good idea to think about the purpose of the documentation. Why are you documenting this? What do you do with the information you documented? How are you going to use this information to do things differently for your tamariki?

When we document children’s learning we want it to be more like storytelling and less like paperwork. We want it to be about the children rather than complying with requirements.

There is no right or wrong way of documenting the end of session korero. Try different things. Keep what you like and tweak what is not working. A key outcome of documenting the end of session korero is to capture the emergent play and learning interests.

This end of session is designed to focus on capturing emergent interests.

Good questions will help you to generate powerful conversations at the end of session.

Capturing the emergent interests on session helps us to make decisions about the next session.

See below examples of how centres document the emergent interests of the children’s play and learning.

Lincoln Playcentre keeps a session profile book for each of their sessions.

North Beach Playcentre captures the day’s learning as a mindmap.

Southbridge Playcentre notes the day’s play and learning on a white board.

River Downs Playcentre revamped their end of session evaluation form to capture the important emergent interests for the day.

I would love to see other creative ways of capturing the stories of the day.

Making Te Whariki visible in Playcentre

Playcentres are frequently asked how they link their work in Playcentre to Te Whāriki. Are we expected to make overt links by writing a strand and a goal on each learning story or can we achieve this in different ways?

Te Whariki is a way of being

In working with Playcentres I have often observed that for many Playcentres Te Whāriki is a way of being rather than a way of doing. In other words they don’t strive to do Te Whāriki, it becomes a way of life. This is very visible in the core principles and how these closely link with the core philosophies of Playcentre. The principles provide us the underlying beliefs of the curriculum, children learn best :

- In relationships with others

- When their family is involved and when their learning is embedded in the context of their community

- When they are empowered through making their own choices

- When we acknowledge the complexity of the learning

Whakamana: Children learn best when they are empowered through their experiences. At Playcentre children actively construct their own learning through play. Playcentre sessions are designed to help tamariki to see themselves as competent and capable learners in that children can choose what they do, how they do it and for how long they choose to do it. Constraints are kept to a minimum.

Kotahitanga: Children learn best when we acknowledge the complexity of children’s learning. A Playcentre we place a high value on play opportunities that allow exploration and experimentation. Honouring the process of the child’s work is more important than the product itself. Learning at Playcentre is integrated into every Playcentre experiences. Adults strive to understand children’s passions and fascination and build on it by providing interesting and inviting play opportunities.

Whānau tangata: Children learn best when their learning is embedded in the context of the community. Being a whānau based organisation, whānau at Playcentre not only manage the centre, but are also the teachers of their tamariki. Most Playcentre whānau attend the Playcentre down the road and as such they bring the community into their centre. Children learn about the community and develop a sense of belonging from the parents working together.

Ngā hononga: Children learn best in a relationship with someone else. Relationships are a key part of successful Playcentre sessions. Good relationships are valued and actively fostered through the cooperative practices. Children experience an environment where they can play alongside their siblings, parents, whānau and other familiar adults. Relationships are often extended beyond Playcentre sessions. People, and the quality of their relationships, are an integral part of a young child’s developing attitudes and beliefs.

Uncovering rather than covering

The intention of Te Whariki is to uncover possibilities, rather than cover specific developmental milestones or knowledge . It does not tell us what tamariki should be learning, but how they learn best. Instead of linking the strands to play and learning outcomes, we can turn it upside down and use the strands to evaluate whether we are creating potentiating learning environments for our tamariki either as individuals or as a group.

The strands are the goals

The strands of Te Whāriki set us some goals to provide a play and learning environment that are rich with possibilities and invite children to participate. Using these strands as a guideline to assess, plan and evaluate will make Te Whāriki visible in our work:

- Mana Whenua: How do we provide an interesting environment where our tamariki feels at home?

- Mana Atua: How do we provide a trustworthy environment where our tamariki can thrive?

- Mana Aoturoa: How do we provide the right level of challenge so that our tamariki are stretched?

- Mana Reo: How do we provide a culture of listening so that our tamariki can share their thinking?

- Mana Tangata: How do provide a collaborative environment where our tamariki can learn to work together?

Returning to the question of whether we need to link our documentation to Te Whāriki? When our programme is embedded in Te Whariki, it seem superfluous to overtly link stories and other document to Te Whāriki for the purpose of accountability. We can expect outside agencies to be informed readers, however at times overt linking can be a good teaching tool for families who are new to Playcentre and Te Whāriki.

How do you make Te Whāriki visible in your centre?

Reference:

Ministry of Education. (1996). Te Whāriki: He Whāriki Mātauranga mō ngā Mokopuna o Aotearoa: Early Childhood Education. Wellington: Learning Media.

Stover, Sue (Ed). (2003). (Revised edition). Good clean fun: New Zealand’s playcentre movement. Auckland: New Zealand Playcentre Federation. Page 38.